(photo from Farm Forward)

I've posted about this before, but the problem is becoming critical. We are destroying our oceans for short-term gain. How can that seem like a good idea?

How about this opening paragraph from an article in Time magazine?

The oceans are being emptied of fish. A forthcoming United Nations report lays out the stark numbers: only around 25% of commercial stocks are in a healthy or even reasonably healthy state. Some 30% of fish stocks are considered collapsed, and 90% of large predatory fish — like the bluefin tuna so prized by sushi aficionados — have disappeared since the middle of the 20th century. More than 60% of assessed fish stocks are in need of rebuilding, and some researchers estimate that if current trends hold, virtually all commercial fisheries will have collapsed by mid century.

This isn't a matter of just skipping your sushi, after we've destroyed our oceans. The oceans feed a lot of people, and provide a livelihood for many more. Of course, that's one reason why it's so difficult to move to sustainable fishing, because it will put some fishermen out of work. But how many fishermen will lose their livelihoods when fish populations collapse entirely?

But there's also a major problem with overcapacity — or the simple excess of fishermen — thanks to the $27 billion in subsidies given to the worldwide fishing industry each year. Those subsidies — especially the billions that go to cheap diesel fuel that makes factory fishing on the high seas possible at all--have created an industry bigger than the oceans can support. The U.N. estimates that the global fleet consists of more than 20 million boats, ranging from tiny subsistence outfits to massive trawlers. Together they have a fishing capacity 1.8 to 2.8 times larger than the oceans can sustainably support. Our tax money is essentially paying fishermen to strip mine the seas.

Get this? We're not just destroying our oceans; we're paying tax money to have our oceans destroyed. I'm speaking about worldwide practices, of course, but the problem is worldwide. Fishing fleets don't just fish in their home waters. In fact, a big problem is factory fishing off the coasts of developing nations, where they destroy the fish that locals need for survival (and where corruption and/or lack of regulation let factory fleets do whatever they want).

As this article states, part of the problem is illegal fishing. But that's not the only problem, since even legal catches are set far, far too high. And indeed, fishing regulations often seem to be designed to let illegal practices flourish.

Right now, for example, fishing boats aren't required to have an identification code from the International Maritime Organization, the only globally recognized identifier for shipping. Establishing the requirement would help distinguish the good guys from the bad guys, particularly if the information is shared among all ports. "Accountability," Flothmann writes, "requires transparency."

Clearly, we aren't serious about this. We are winking at illegal fishing (probably due to rampant corruption in many countries), and we're encouraging overfishing even by legal means. Unfortunately, everyone involved sees a short-term gain in raping our oceans, while the long-term disaster will fall on someone else's watch.

Farm Forward has a good article on this, too:

Humans are consuming marine animals in such massive numbers that the balance of ocean life has already been drastically upset since the beginning of large-scale industrial fishing in the 1950s.

The culprit for this sudden change in the ocean’s ecosystem is what University of British Columbia scientist Daniel Pauly describes as “fishing down the marine food webs.”1 What this means is that overfishing of alpha-predators like tuna and salmon—whose populations are rapidly dwindling—has caused us to begin eating lower down the ocean’s food chain. In the absence of their predators, species a step further down the chain experience a temporary population boom, creating an illusion of abundance for fishers, who begin the process of fishing them out of existence—and so on, all the way down to bottom-feeders and, eventually, plankton.

If this trend continues unabated, Pauly suggests, the future of seafood will be an unvarying supply of “jellyfish sandwiches.”2 An initially skeptical scientific community has confirmed Pauly’s fears, even going so far as to project an approximate date by which the world’s seafood supply will have run out based on the current rate of ocean fishing: That date could be as soon as 2050, according to a 2006 paper on the effects of overfishing published in the journal Science.3

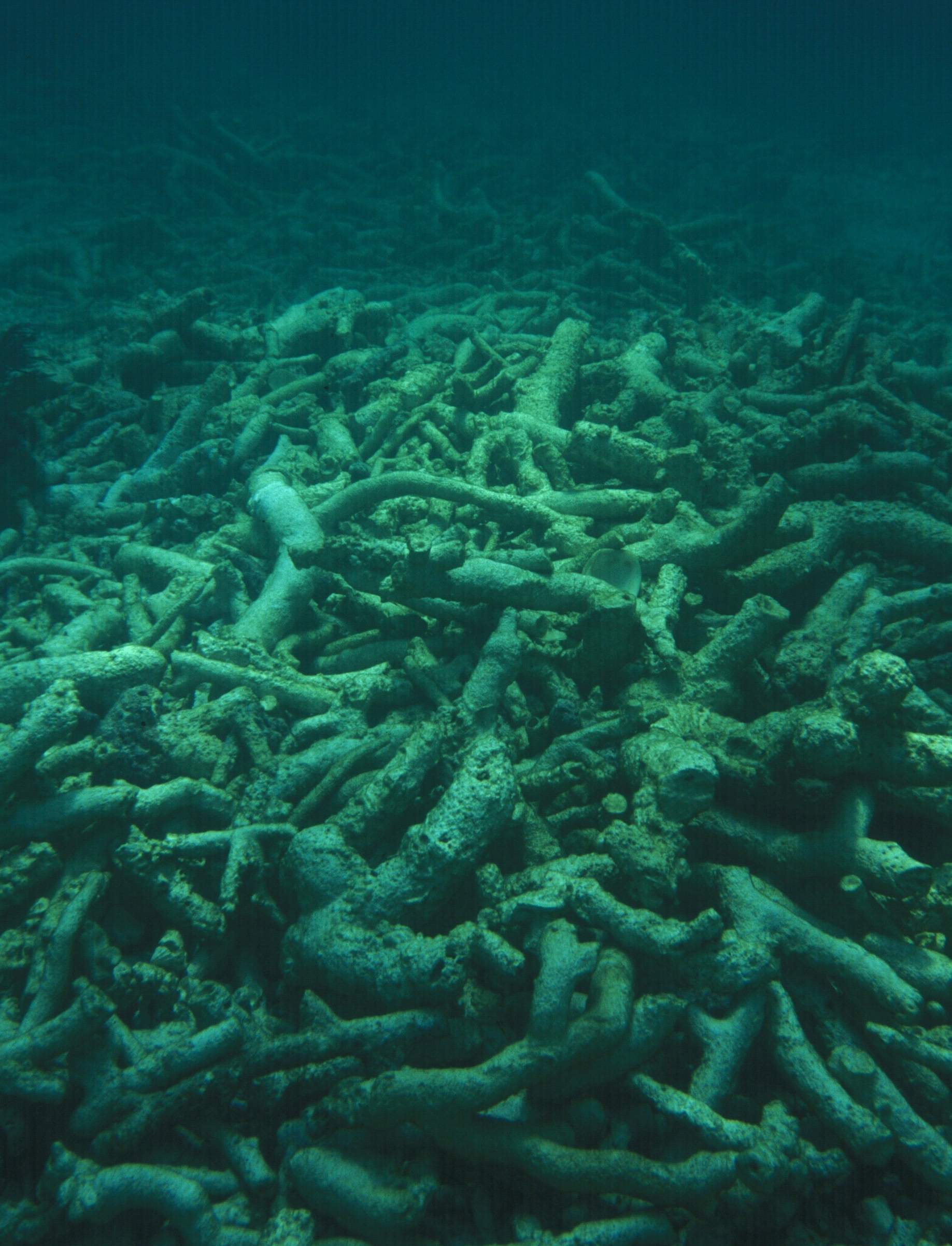

And fish are not the only marine animals to suffer from aggressive commercial fishing practices. Techniques such as “bottom trawling” (in which nets are dragged thousands of miles across the ocean floor) and longlining (using large numbers of baited hooks on an extended line) indiscriminately destroy entire habitats of deep-sea species and devastate populations of dolphins, whales, sea turtles, seabirds, and other marine animals who are trapped in the nets or hooks as “bycatch.”

It's not just overfishing, of course. Global warming is destroying coral reefs, not simply because of increasing ocean temperatures but also from ocean acidification. But even here, overfishing is also a culprit. Removing one species can change a whole underwater ecosystem. And the cumulative impact is just devastating.

(photo from SurfThereNow)

We're not talking about the far future here. Many of us will still be alive a few decades from now, when projections warn of an almost complete collapse of ocean fisheries. Certainly, our children and grandchildren will face the tragic results of our ignorance, apathy, and greed.

I'm a science fiction fan, as well as an environmentalist. One prominent SF theme has always involved turning to the oceans, after we've made the land uninhabitable. But in reality, we seem to be destroying our oceans even faster than we are the rest of the planet. This wasn't the future I'd hoped to see, not at all.

And I remember as a child learning about the old whale hunters, how they'd driven whales to the verge of extinction, until the industry itself collapsed for lack of new prey. But you know, that was taught to me as a lesson that we'd learned. Now that I'm an adult, I realize that's not true. We still haven't learned that lesson. I'm both astonished and disgusted to realize that.

Will we ever learn it? More to the point, will we learn it before it's too late? Or will our descendants look back in astonishment at how stupid we were?

No comments:

Post a Comment